BETT 2026: Sir Mark Grundy reflects on 28 years of school leadership and education innovation

Speaking on the BETT 2026 main stage, Sir Mark Grundy and Mick Waters reflected on nearly three decades of school leadership, examining how technology, curriculum design, and trust-wide culture have shaped education and what leaders need to hold onto as AI and structural reform accelerate.

At BETT 2026, a session titled Leading change: Sir Mark Grundy on twenty-eight years of innovation brought a long-term perspective to a conference otherwise dominated by AI announcements.

The conversation, led by educationist Mick Waters, focused on how leadership decisions made over decades, not technologies adopted in moments, have defined school improvement. Waters was joined on stage by Sir Mark Grundy, CEO of Shireland Collegiate Academy Trust, who is preparing to retire after almost three decades in school leadership.

Leadership as service, not control

Opening the discussion, Waters described Grundy’s career as spanning “some of the most exciting and turbulent periods in our country’s educational history,” before asking what the term collegiate truly meant in the context of the trust Grundy founded.

Grundy responded that the concept was rooted in service rather than hierarchy. “For us, collegiate has always been about people,” he said. “It’s about creating a culture where staff understand that leadership is about serving others, serving the staff, serving the children, and serving families collectively.”

He explained that collaboration across phases, subjects, and roles was intentionally built into the trust’s structure from the outset, adding that this was not an add-on but “part of the DNA.”

Technology as infrastructure, not a solution

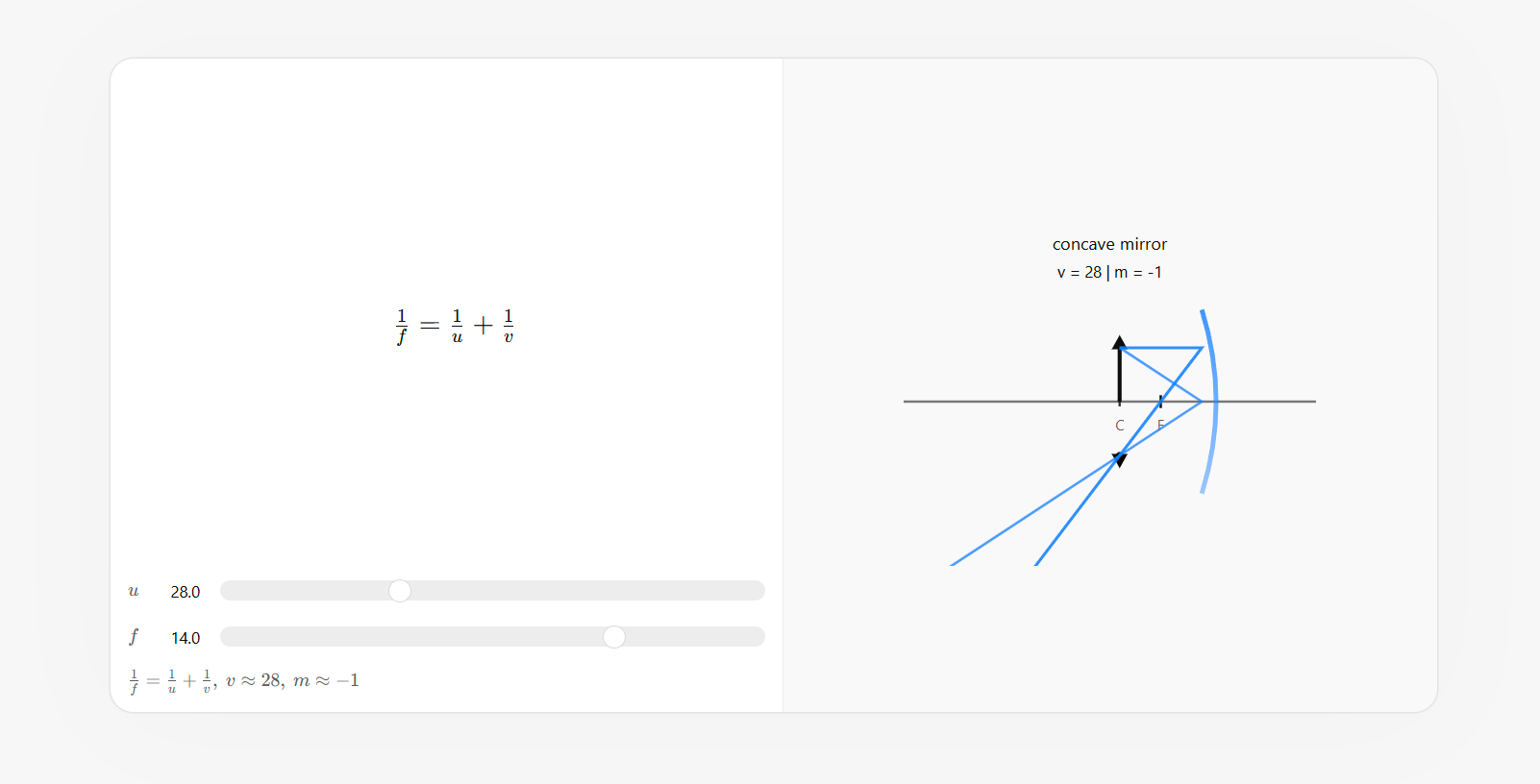

Waters noted that Shireland is often cited as “big on technology” and asked how that reputation developed. Grundy rejected the idea of technology as a silver bullet. “Technology has never been about replacing people,” he said. “But it can take a massive amount of pressure off people, and that matters.”

He described technology as a leveling tool, enabling schools to reach into homes, support families, and reduce operational friction. He stressed that the trust’s approach had matured over time. “Twenty years ago, I probably didn’t have the discipline I have now,” he admitted. “Today, when I walk around BETT and see amazing products, the question I ask is simple: what will this actually give our children?”

Grundy added that technology should “do the heavy lifting,” freeing teachers to focus on teaching and relationships rather than administration.

A recurring theme throughout the session was what Grundy described as an “architectural” approach to school design. “We’re very architectural,” he said. “We use technology to create structure, and that structure gives people the freedom to do amazing things.”

He argued that clarity, consistency, and shared systems allow teachers and students to understand expectations, navigate schools confidently, and build trust with families. Technology, he said, enabled this architecture at scale, particularly within a multi-academy trust. “It’s not scripting lessons,” he clarified. “It’s about creating the infrastructure so creativity can happen safely and consistently.”

Rethinking Key Stage 3 and curriculum design

Grundy explained that nearly two decades ago, the trust made a deliberate decision to rethink Key Stage 3, concluding that it did not serve students as well as it could.

“We asked ourselves how to build the best possible bridge from Year six to Year seven,” he said. “For many students, that transition is overwhelming.”

In response, the trust adopted a thematic curriculum model in Years seven to nine, drawing on primary-style approaches and gradually tapering toward exam preparation. This curriculum was supported by an online platform co-created by staff. “Having an online curriculum that opens learning to staff, children, and homes is incredibly powerful,” Grundy said. “But what matters most is that it’s co-curated. People share the effort.”

Waters pressed Grundy on the trust’s decision to retain arts, design, and technology as central curriculum elements at a time when many schools narrowed their offer. Grundy was blunt. “The English Baccalaureate was not my favorite policy,” he said. “We rebelled against it.”

He argued that memorable learning experiences often come from performance, creativity, and cultural exposure, not just exam content. He highlighted the trust’s partnership with the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, which supports a school where students can access world-class musicians from an early age.

“I’ve seen students go from never touching an instrument to Grade six within a few years,” he said. “That’s why I came into education. To give children opportunities.”

Staff retention through growth, not churn

Turning to workforce challenges, Waters asked how the trust has navigated recruitment and retention during a period of national shortages. Grundy said retention had been a strength. “We grow our own,” he explained. “We invest in people, and we give them reasons to stay.”

While acknowledging that some staff leave to take on new challenges, he framed this as healthy rather than harmful. “If people go elsewhere and do great things, that’s part of the ecosystem,” he said. “What I don’t understand is unnecessary churn driven by systems that don’t trust people.”

AI, caution, and leadership responsibility

As the conversation turned to the future, Waters asked Grundy about AI and emerging technology agendas. Grundy described AI as unavoidable but manageable. “Whether we like it or not, AI is not going away,” he said. “But it has to be led. It has to sit within a framework.”

He argued that AI should be used to reduce workload and support communication, not replace human judgment or relationships. “It will never replace human connection,” he said. “But why wouldn’t we use something that can reduce pressure on everyone?”

Retirement, trust, and what matters

Reflecting on his upcoming retirement, Grundy said the hardest part would be leaving daily contact with schools. “I can walk down the corridor and see children learning,” he said. “I will miss that enormously.”

What he will not miss, he added, is unnecessary bureaucracy. “My whole career has been built on trust,” he said. “If you don’t trust people, you can’t improve education.”

Waters closed the session by reflecting on Grundy’s impact beyond policy or structure, telling the audience that his influence would be felt long after formal roles ended. “There will be children all across the world who will look back at moments in Shireland schools and remember them with affection,” Waters said. “They’ll remember the difference those schools made to their lives, to their world, and to the world that we all live in, for the better. Throughout your career, you’ve made a difference to children day in, day out, and that’s what really matters.”

ETIH Innovation Awards 2026

The ETIH Innovation Awards 2026 are now open and recognize education technology organizations delivering measurable impact across K–12, higher education, and lifelong learning. The awards are open to entries from the UK, the Americas, and internationally, with submissions assessed on evidence of outcomes and real-world application.