Will AI-led innovation improve or worsen social justice in US schools?

Artificial intelligence, or AI, has become the go-to solution for any concern in any sector you can name. Advocates feel that implementing AI-based innovations in schools can provide better access to learning resources and prepare students for a changing future.

However, many educators are unimpressed by the issues AI has seemingly worsened in academia. More plagiarized (now GenAI-created) submissions. Low application of research skills due to the convenience of smart searches.

Perhaps, its biggest risk is the possibility of worsening social justice in an already precarious socio-cultural environment. So, which facet of AI will prevail? What does it mean for present-day students and professionals?

AI is making the learning process more customized

A preliminary component of social justice in schools is ensuring that all students receive the support they need with their learning. It may not be happening in many US schools today, at least according to several surveys.

A 2023 Pew Research Center noted that 51% of US adults feel the public K-12 education system is heading in the wrong direction. They are dissatisfied with the low attention to subjects like science and mathematics. Another concern is that educators sometimes bring personal views on politics and other issues into the classroom environment.

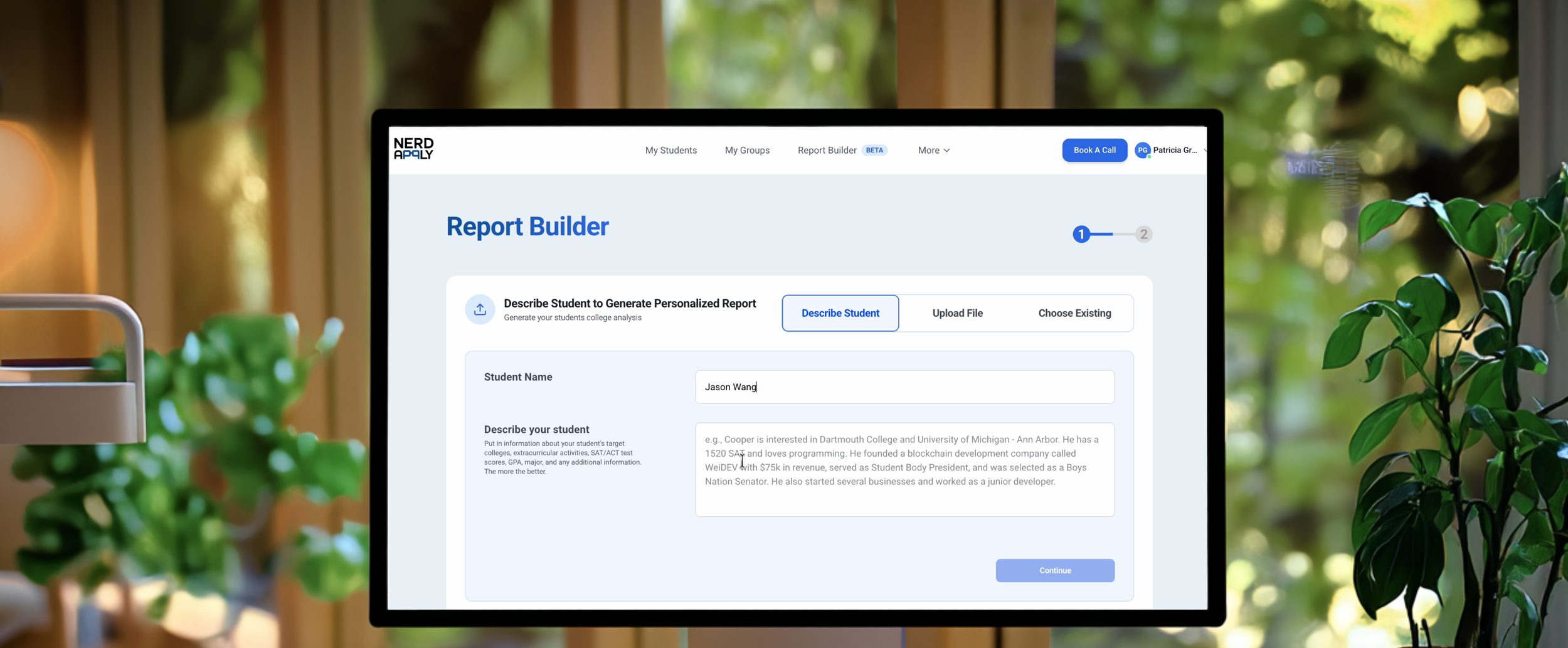

In contrast, AI-based adaptive learning platforms can check that the content and delivery adapt to the personal strengths of each student. Tutoring systems can now use advanced learning models to assist students with doubts and queries. These tools can support a student’s academic journey in a way that human teachers dealing with 20+ students per class may find unmanageable.

Making AI work needs socially sound leadership

Leaders will play a pivotal part in steering artificial intelligence toward student-friendly outcomes. In the absence of strategic leadership, educational institutions making such changes could impact social justice.

For example, most AI applications require considerable data collection. It could include details of a student’s family and income levels. Unless the tool is stringent about data security and privacy, the institution using it runs the risk of invading an individual’s privacy. What if third parties use the collected data in ways that worsen social conditions, especially for low-income students of color?

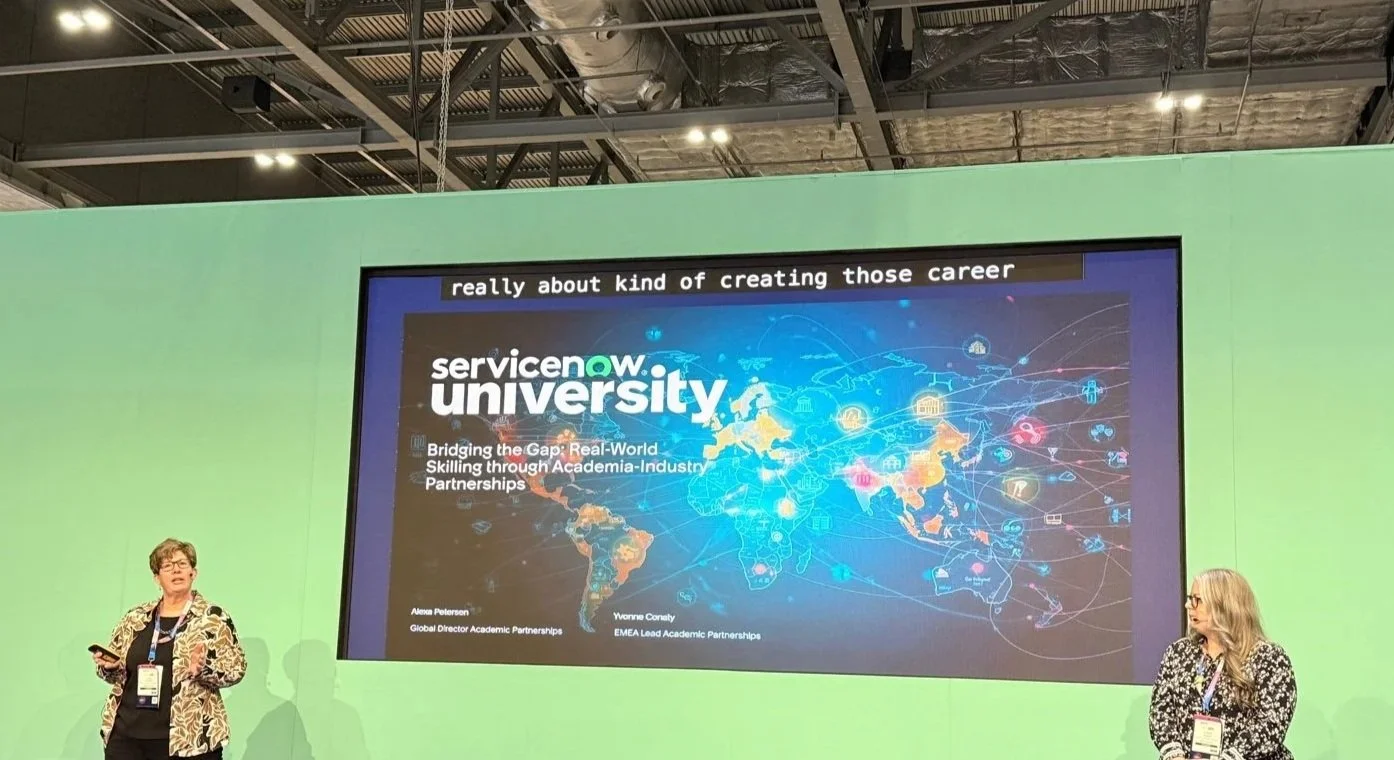

Guaranteeing that any organizational change has a sharp ethical and moral compass requires conscientious and sensitive leadership. Some professionals choose to pursue a Doctorate of Education online or other terminal courses to gain a deeper understanding of implementing change in public and private organizations.

Such programs can help them apply well-researched academic models to real-life situations. Since they use an online delivery format, professionals can balance them with their careers, enriching their learning with on-the-job experiences.

Some US schools now offer upskilling opportunities for their staff to empower professionals with digital literacy and best practices for data privacy. Educational institutions planning to adopt an artificial intelligence tool have much to gain from consulting with change agents.

Marymount University notes that professionals can benefit from reflecting on transformational leadership principles to drive social change. They cover the self, the organization, and the community, offering a complete, 360-degree view of a proposed intervention.

Addressing the neutrality, or lack thereof, of AI

Many routinely assume that artificial intelligence will be more neutral than educators who overtly assume a specific political stance. Unfortunately, AI can often be biased. Herein lies one of the prime reservations in adopting these tools for driving social change.

A 2024 study published in AI & Society highlights that the bias in AI often emerges from a lack of diversity in the training data. Algorithms that use skewed historical data can suffer because of years of racism and socioeconomic inequality.

Consequently, they may deliver unfair results for some students (typically non-native English speakers). It shakes the very foundation of tools like automatic grading systems and personalized learning platforms.

What’s worse is that the bias in AI may be subliminal, emanating from a skewed algorithm, a black box for many users. It can be more damaging than a professor who assumes a blunt stance (and can, therefore, get dismissed as a flawed human).

Ongoing research attempts to make artificial intelligence applications fairer. It will take concrete work at the developmental level, starting with having diverse voices on the team. Until then, educators must stay cautious while using AI tools in student-centric capacities.

The long and short of it is that AI deserves careful enthusiasm, much like any other technology in education. Its capability is limitless, but so is its risk of perpetuating social inequality.

US schools, as prominent members of the American community, should look at partnering with researchers and policymakers. It will help them assess the optimal implementation of AI in their programs. Ultimately, artificial intelligence applications require deep human insight for their development to mitigate the risk of prejudice.